Hello and welcome back to Walking With Goats, my convincingly arrhythmical invitation to sit-in on the gore and manure fest that is vanity-smallholding at the beginning of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

I left you a while ago. Let’s touch base with that.

Easter.

There are so many seasonal rituals that lie washed up on the beach of societal amnesia now. Shrove Tuesday for instance; a merry trip down the garden path to pay hyperinflation rates on six regulation issue, date-stamped eggs laid by chickens confined to tortuous influenza-sheltering lockdowns under 24 hour Guantanamo mood lighting to increase yield. Or roast lamb on the Bank Holiday dinner table with family, its oxen-sized cutlets fresh out of the meat nappies that have cradled it over 8000 miles from Jacintha Arden’s shores.

Vegan pancake recipes and precision-ferment burgers can help us to heal this rift between tradition and our guilt-riddled modernity – but only at the expense of California’s water table, the global bee population or the integrity of our genome.

All in all, nothing says spring in the twenty first century like the gift of a stigmata greetings card and a chocolate egg.

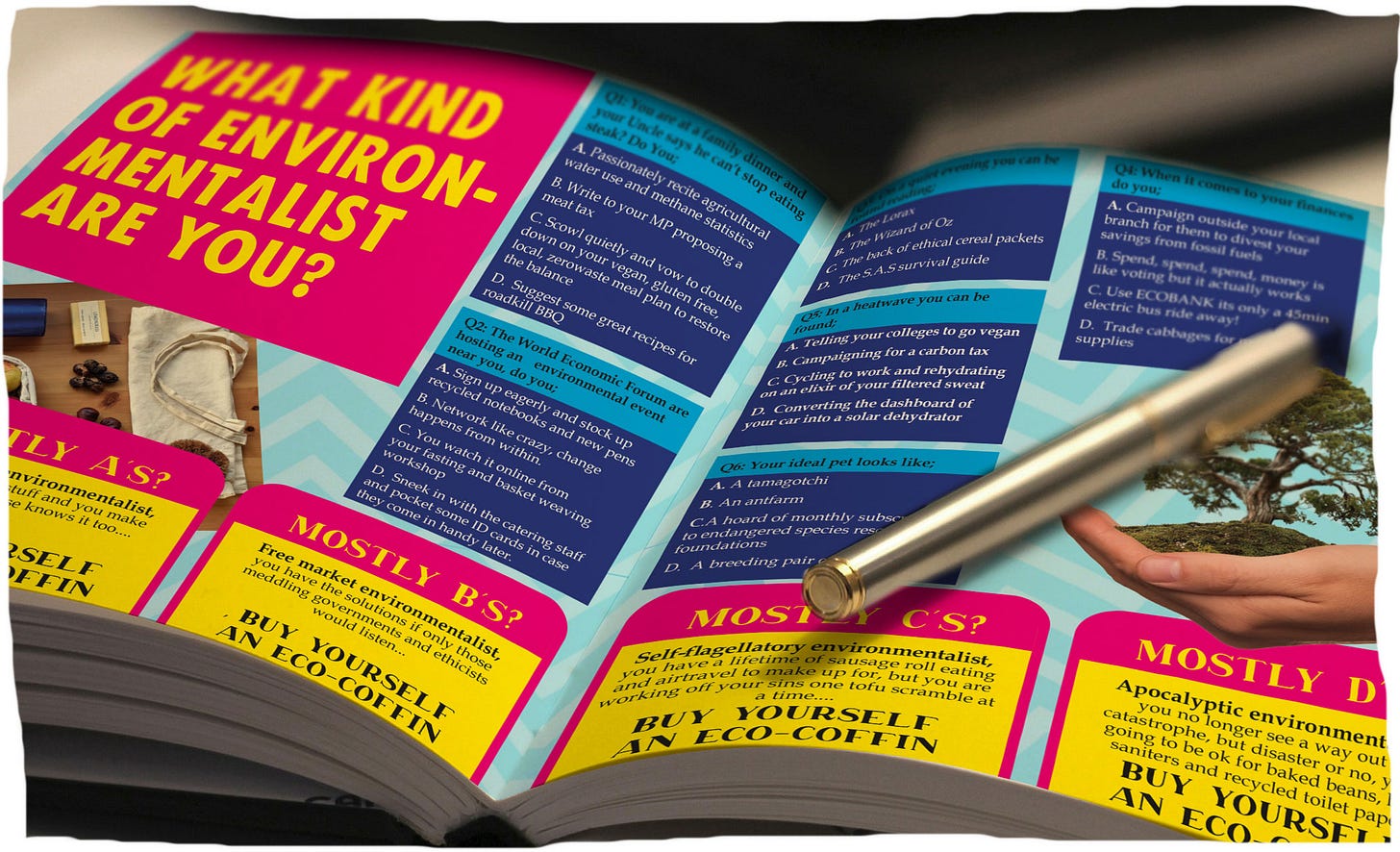

Rarely does our local primary school hit the cultural nail on the head so squarely – so that it’s really only now, here, sitting at the apex of summer, that local Gen Zed kids and their not-yet-eco-coffin-bound parents might find themselves seeking a new seasonal moment of self-flagellation to wash off the existential guilt.

Original Sin had nothing on 2022.

My deeply inculcated masochism, however, has really got some purpose now.

Having lit upon the only vocation more brutally self-defeating than full length fiction, I’m happy to present you with my bloodied hands. Let me take you through my last two months of almost self-sufficient smallholding: not so much a sojourn into farming, more a collage of Dr Dolittle and Primal Survivor. A churning, overturning symphony of death and life, all authentically swimming in a pool of shit-streaked mud.

It's hard to know which to start with. While on the surface, this question seems a no-brainer, in fact the emergence of new life is only occasionally, and only marginally, less brutal than death when it comes to subsistence farming. I will carefully illustrate the veracity of this statement with the tale of the chicken-duck, or dicken-chuck, or indeed chuck-dicken, Charles Dickens.

Before we sink into the Shakespearean anguish of Charles Dickens’ relationship with its tragically devoted duck mother though, it’s worth asking if death is really that off-putting. I have two anecdotes with which to explore this question, both of which – I hope – offer a counterpoint to the shiny banality of immortal consciousness and NFT stockpiling that is currently being packaged for us as a spiritual revolution… proffered benignly by modern icons like dandy, space-saving Jeff Bezos and his roomier transhumanist friends.

This episode of Walking With Goats takes in few steep hills and precipitous valleys. Feel free to stop for lunch without me, or indeed order an Uber if you need to – although I can only presume that if you’re accompanying me on the journey at all, it’s with a morbid fascination for the exertion.

Most people, I think it’s fair to say, would struggle to delineate a clear picture of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, even though it’s happening to them (which, interestingly, is something that could also be said about death).

The “progress” housed under the mantle of 4IR is complex, sweeping and deliberately obscured from our view. Nonetheless, it is of the utmost importance that we understand it.

Goats view progress with a detatched eye until they have thoroughly determined its utility. A new shed could house many things. Their staff, ever industrious, are not always to be trusted, regardless of how well they may perform their duties.

We the humans, on the other hand, are not so circumspect. Why do we not also sniff a thing for a while after its miraculous arrival?

Here in the West, we’ve mostly ceased to view ourselves as prey. We don’t spend time in awareness of death; an oversight so vast within the small room of our lives that only really fucking exceptional television could keep us from bumping into its elephantine shape. The first time in my life that I was brought up short by it, I was shocked enough to have to write a book.

Unsurprisingly, the audience for books that mention death in the first sentence is small. But death is – when the subject is broached at the dinner table for instance, in suitably impersonal manner – in fact a subject of voracious interest to many. Few topics of conversation elicit the level of fascination from strangers induced by the mention of producing my own meat.

The questions are invariably veiled with the etiquette of omission.

“Do you… do everything?”

Cosmetics is the nemesis of real morality and the modern industries of meat and dairy act as a telic example of it – or at least can claim such an apex until 4IR’s complete.

Feeling that I ought to “do everything” is what led me down this path. But the reality shrouded by layers of shiny packaging on our supermarket shelves is impossible to encapsulate in a single essay. It’s etched in my memory with images such as the angel wings of Hercules – our first drake, the first life I ever took – wheeling in the darkness as his disembodied head lay dying on the wooden stump where I had severed it. Two separate parts of him, losing life in synchronicity.

The reality is vast; it shatters world views. It is carved in grief and compassion, grace and horror. It is the other face of what it means to live.

Ducklings and baby chicks are so difficult to keep alive that Fran and I are now discussing adding a great big fucking snake to our amorphous community permaculture system in order to utilise the constant supply of free food. I’ve eaten puff adder. It was delicious and ours would be a fat one.

Having lost entire, successive clutches of ducklings in the supposed sanctum of their own house to rat massacres stimulated only by bloodlust and leaving heaps of corpses (and this despite shutting myself into the rat infested shit box for days to screw viciously flailing razorwire onto the suffocating walls and ceiling around me) I will briefly leave as a breadcrumb to those interested in raising poultry, two words of wisdom from an older world, a world now almost lost to memory: mushroom feet.

Our new duckhouses will have mushroom feet.

This year I couldn’t bear it. This year I couldn’t shut another clutch in and lie praying silently at night. No, this year I let the mothers take them to the pond – for the buzzards.

As I watched the last of Clara’s brood fly off as a fat yellow mouthful, I ruminated on the grief of losing lives which, if they had in fact been male, I would have taken myself in a few months’ time. Such is the stomach churning cycle of futility not glimpsed through the bright reflections on cellophane.

I turned my hopes to Lemonade.

Unfortunately though, I was not the first.

Chickens are wily creatures, far too intelligent – and indeed caring and socially nuanced – to be subjugated and abused en masse, as our species sees fit. Chickens have nous and, contrary to their reputation, ducks – or muscovey ducks at least – are imperturbable mothers. Where better to lay your eggs as a footloose and fancy-free career chicken, than deep in the middle of a muscovey duck’s nest?

Charles Dickens hatched – as all chickens will – in 21 days. Duck eggs, regretfully, take 35. And ducks are programmed to abandon the nest and care for their live young after a certain wait. With Clara’s brood all gone, Lemonade’s single yellow child must have seemed a precious life indeed.

It’s just a shame that baby chickens drown in two inches of water.

Charles Dickens was born to a destiny of isolation. For as much as the stuffed sock, warmed in the oven by my daughter, satisfied Charles Dickens’ basic needs, it could not offer him any shelter of the heart. And Lemonade, rejecting all eggs to a future of optimistic incubation in my scullery, mooned only for Charles Dickens as she sat beside the pond situated closest to his chirruping cage.

But at least he lived. Not so Duck Dickens, the sister duckling I excitedly cradled after its incubator hatching and carried to the bereft Lemonade. No. Lemonade would have none of it. A reassuring five minutes of mild neglect was superseded as swiftly as my leaving allowed. Duck Dickens was not welcome. I can only presume, on the basis of what I found, that Lemonade shook her to death.

Snake food.

I could offer you a further roll call, in this minor key moment, to illustrate the abject desolation of life’s revolution of souls, as ground into my consciousness by smallholding:

Cello, the next Emergency Chicken, who hatched as I watched with deep dismay, in Dilys the Duck’s nest a few weeks later – to spend some days attempting to climb the career ladder Charles Dickens speedily, and with violent pecking, moved to withdraw – and who failed. Happy enough tucked into my bra during the day. Passed away in a cardboard box overnight. Snake food.

Our dog Gripper, after thirteen years of dutiful service, sent off with bouquet and frisbee to a grave in our memorial garden. Worm food, I suppose.

Noah, the tup whose life I took for my own table.

And Moana – who could not be eaten, despite my greatest effort – and whose story deserves to be told in full.

Or perhaps finally, at the infinitesimal end of the living spectrum, the spider that fell from the sky.

The statistical likelihood of this spider, which had presumably lived happily in the rafters of my bedroom for some time, descending gracelessly to land in any environment unfavourable to it were slim. What spider dangers could really lurk around my bed? As much as I’ve spent years suppressing my loathing of arachnids for the sake of my daughter, I’d never kill one. How unfortunate then that, upon its sudden, directionless fall, it should find itself having targeted the tiniest of baths, filled to the brim with birdseed-swimming liquid. Helpless and squirming, when I lifted it delicately out upon a pair of nail clippers, how doubly unfortunate that it should encounter the figure of Charles Dickens.

Not a duck, despite the unending hope of its mother, there was nothing remotely ducklike about Charles Dickens’ long, agile toes or sharp, able beak. Our initial fear that he might represent some strange progeny of the duck raping cockerel we’d been forced to confine to a cage upon its repeated pillaging trips to the pond had now ebbed. It was quite clear that – although he spoke a creole of sparrow and human and lived in the dolls’ house furnished for him by my daughter – Charles Dickens was a chicken. He had everything a chicken needed to survive and thrive.

Luck can be poorer than a capricious universe of random collisions is capable of offering, you’d think.

Fran and I have a word - a verb - to kaspar. Like most mothers, we are the stewards of a number of small, random pebbles, on mantlepieces, bookshelves, in wallets and pockets. Collected in the thrall of now forgotten walks or picnics, during which their shining facets spoke of eternal memorability, in their years-dulled state they will occasionally fall and break things or perhaps get hoovered up.

Now, however, we have begun to return these stones to the rivers of their own journeys. Now, with ceremony, we place them into our compost bins. To kaspar – so named after the online dating profile that Fran was scrolling through as we discussed this concept, and who’s long since returned to the unmarked horizons of the internet – to kaspar is to re-join our fundamental path.

So, here, a special kaspar, offered for all lives lost this spring. Here, a kaspar for them all.

And I will leave Charles Dickens – who, it turns out, is not a he at all but a she, now well-accustomed to preening alone, devoid of siblings to brutalise, on the perch inside her shrinking cage like a ship in a bottle – I will leave her at the most decisive moment of her life. Gazing down at that bedraggled spider in front of her and - for the briefest of instants - not responding, all her millions of years of evolution chafing for the very first time against the only environment she’s ever known: one of duvets and egg cup fountains and tissue-box sofas.

I will leave her, experiencing the pull of the real.

It's necessary to divide this episode, because of Substack’s capacity, and maybe yours as well, and so I will split it here, between birth and death.

We’ve recently been informed that the best babies we can have as the C21st century “progresses” are virtual. VR headsets strapped to our faces, digital gloves of sensory input upon our hands, we can look forward to sating the carnal urge of motherhood by feeding a mouth which will never be able to call upon the resources of a planet we’re assured cannot sustain us.

I wanted to know what it cost for me to live. That’s why I started this; a lifestyle that has successfully eroded all forms of modern joy. I wanted to know what it cost for me to live, in milk and meat and potatoes. I wanted to know if I could manage to sustain myself.

I believe at this point that the answer is yes – although perhaps not if I wish to recline on a tissue box couch, plentiful as the pre-softened, protein-balanced feed may seem, so conveniently placed in the eggcup beside it.

I believe that I can feed my non-virtual daughter.

Here in 2022, we’re entering a time of joyful, volunteer eugenics, in which the similarity to Huxley’s Brave New World might be uncanny, if not for the other text that his brother wrote – less iconic but certainly no less seminal.

This morning, Bill Gates offers me a peek at Agile Wallabies as I sit within the natal blue glow of my screen.

A passive appreciation, we are told frequently – and by reassuringly familiar voices – is now the best way that nature can experience us.

Conservation has a mucky history, fraught with nasty ghosts, and is no more innocent in its 21st century iteration. As if the leering drawl of Prince Charles wasn’t enough to put you off in itself, its banner is currently waving over policies that will see rural Wales flogged to New York and Tokyo hedgefunds in the name of sustainability. Further afield, Masai herders are herded at gunpoint off the landscape of which they are a living part. At its core, conservation severs the human from its ecosystem. And we are all a living part of the land.

Cui bono? As impending war is added to the catalogue of dynamics currently pushing Westerners into non-sovereign states of dependence, it’s worth interrogating the reasons why the choice we might have to live from the land is so deftly being removed.

For nature’s sake, we are being told to place our faith in the benign entities of Blackrock or Vanguard – now Naomi Klein-approved World Economic Forum “stakeholders” – while they reconceptualise its ecosystems as stock exchange asset classes for which they modestly suggest themselves as steward.

If we love nature, we are told, we need to socially distance from it.

In May I made terrariums to decorate our summer party (an event we intend to make annually, and to which I hope you’ll all come next year). That week I was also building up to take Noah’s life. And I couldn’t help but think, as I prepared for that experience, of the newly seeded landscapes captured in perpetuity within those jars as an apt metaphor for our lives inside 4IR. Somewhere between the nascent, swelling beansprouts and superglued rock formations, a tiny George Monbiot was enjoying a sponsored walk in colours that matched the Ukrainian flag.

Fed by the leafy, logo-bedecked systems of our post-agricultural world – the inputs and outputs of which are carefully obscured from us – here we sit, assured of our own harmlessness, each in our panopticon terrarium.

To make ourselves superfluous to our own survival is to drain our lives of meaning.

There is no wild inside the carboy glass.

Images by Fran Sivers, with special thanks to Spoon Graphics.