Dear friends,

I speak to you across a distance, hoping – as I always do – that my words will reach you closely and in confederacy. We’re separated after all, other than at heart and by the bridge they make.

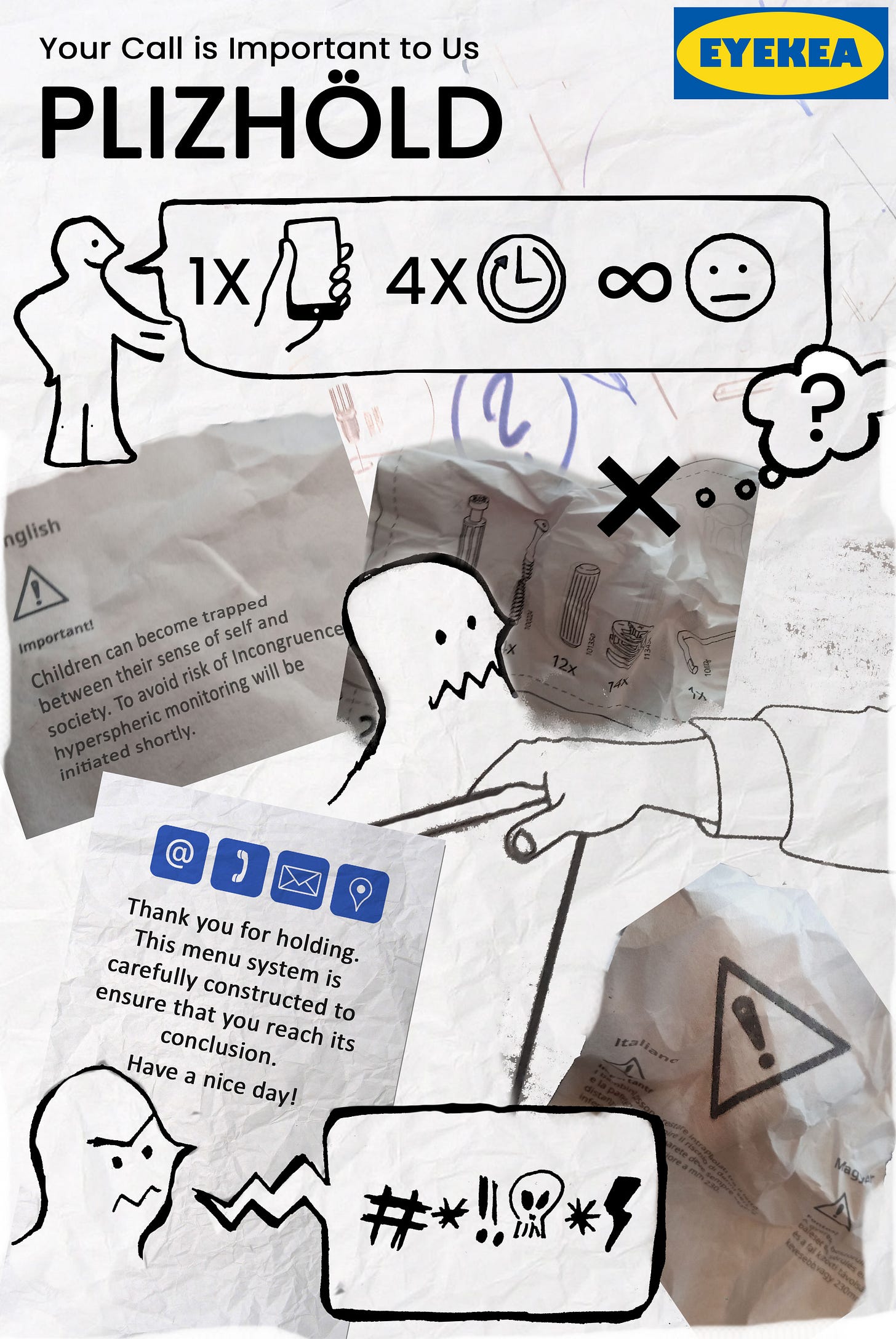

I want to talk to you about this.

There’s a great deal of separation now, I find. Globally harmonised to the frequencies of flowing data, we each sit alone. Communicating instantaneously, streaming, chatting, tweeting, all of our real backgrounds blurred, we can customise a thousand skins across our pixellated faces, yet the chamber we occupy is generated for our solitary preconceptions.

I hope you’ve had the time to be outside. These two worlds, I’ve felt recently, have never been more different. The hours are long in the vegetable garden for me now.

May danced with us in all her finery, and a finer May we never saw. The only cloud in the sky was the willow seed; a nascent forest floating amidst the blue. It’s so long here between our summers that by the time one comes we have forgotten what it is. The quality of the light has lost its name. Kept a secret by Mid Wales, withheld in nine wet months of winter, our summertime becomes a stretch of unexpected grace.

My work makes my writing less frequent. I am sorry for this, as I’ve said before. The entire cabbage supply has been in need of intensive care. The goats must be walked, and these days of course, Lucy and her two young lambs want to come in convoy. Kama bullies her – bullied as she is herself by her stronger sister – and there’s much clashing of heads as Lucy bullies the baby goats in turn. But she is flockless now, apart from these strange field-fellows.

How strange all our own field-fellows are as well, I think when I do sit at the laptop. I put the blog out on Twitter. I survey the landscape so agitated by Elon Musk’s new algorithms. We find ourselves lost in a flock that’s not of our choosing.

In every corner, conflict roils. There’s ever so much to debate. Gasses in the atmosphere and different concepts of selfhood, gods and demons and rulers, the filigree weakness of one financial susperstructure or the next. The disputes grow louder with every moment someone goes unheard.

And yet I’m certain – here in the living silence of Mid Wales – that everybody everywhere shares this same silence really.

It’s been my devotion, in writing – for more than two decades now – to try to find the right words to bring to the surface the world which we experience in our own quiet. Words that voice confidences held inside ourselves.

Language is power, I tell my daughter.

And it’s being used against us. Subsumed in cacophonous words which have lost all meaning, we’re missing signals of truth. For this reason – as well as for the sake of a profound experience that has taken place in my life since I last wrote to you – this episode of Walking With Goats is offered, for good or ill, in respect of hidden things.

Concealed within a tall beech hedge which alternates – green then copper, every other – and which was raised and long-nurtured by my mother, our vegetable garden stands sheltered from the changing tempers of the world. Since 2020, as I have described before, it has been greatly expanded. Adjuncts continue to grow year on year and slowly we manage to fence them into safety. Couched in the quiet centre of the property, its temptation to all surrounding creatures – wild and kept – acts as a challenge of similarly increasing proportions.

And what creature loves to create challenge more than the goat?

The scent of the secret, the undisclosed frisson of the disallowed – these are the hints upon which goat evolution has sharpened an acumen of unrivalled competence. Yes: they know there is a thing you don’t want them to know of.

Hua is naughty. Of course, all Baby Darlings are naughty – but since eschewing the bottle offered her in morning compensation for her mother’s milk, gazing at me with her prettily narrowing eyes – Hua has set her sights on rivalry. She cannot understand why I exist – and why it is that I keep turning up – but since I do, she most certainly will not trust me.

It was no surprise to me therefore, when I discovered her hanging almost vertically in the spiky lower claws of the vegetable garden hedge, having vaulted through from the adjoining field. Entangled in a mix of beech branch and wire, she hung safe but suspended by both pretty ankles; utterly immobile.

I stood between the rows of plump green kale and looked back into those narrowed, wordless eyes.

“Hua naughty,” I verbally conceptualised for her.

Sometimes the free-thinking need a little help with definitions.

The Darlings have only two states of being: Naughty or Happy. They can be Happy in their Nice Field, Happy in their Nice House, Happy on a Nice Walk or, when the growth is best elsewhere, Happy (on a tether) in a Nice Place.

If they are not Happy in any of these situations, then by default they must be Naughty. And if there is any confusion as to the potential for these two states to overlap, then it’s the Darlings’ confusion only.

For a long time – forty years in fact – I was also Happy in my Nice Field. If I vaulted fences, they were only of the low and teasing kind. The grass was plentiful, raised as I had been – with land, and health and education. In my 20s, I married a South African and came to visit far less gentle pastures. Though it was true that I watched sickness take hold of and eventually claim some I was close to – leaving the pharmacy with a suitcase-sized carrier bag for my father’s autoimmune disease every 3 or 4 days for instance – generally speaking, the view seemed fairly unmarred as I surveyed it above my hedges. I had no reason to suspect any issue greater than the standard ones – of incompetence or selfishness – on the part of the farmers of my world.

Above the vegetable garden, sheltering the three buildings that encircle our yard, the larch woodland my mother has stewarded throughout those forty years bears its new green pennants with joy as the summer comes. Home to a gradually increasing understory of native alder and beech (as long as no goat is Naughty in the vicinity), its grass is long and lush and can, as I have mentioned before, give a good meal to a small flock of less destructive sheep, when the spring hasn’t yet offered growth for them elsewhere.

There is one tree though under which the sheep will not graze, despite the fact that its grass is richer and greener than any other’s. Approaching the swathe beneath the Hanging Tree, every one of them will sniff the ground – a space of ten square feet maybe – and then move quietly on. They don’t need to raise their heads to see the gantry over them.

We slaughtered Obsidian in the first week of May. He was sharper than the average sheep. Child of Lucy, she had taught him that I was the bringer of both food and justice. For twelve months, unlike any other ram I’ve known, he was affectionate and gentle. And then this summer, Obsidian changed. After a year of stroking his head and scratching underneath his chin, allowing him to take the lion’s share of Yummy One, he attacked first my daughter then me. He decided that, henceforth, there was to be no more conducive a relationship.

I take the shot myself when kills are made here, in order to be aligned with the reality of what my life entails. But on this occasion, alone in her field, Lucy wouldn’t move away from the fence from which the Hanging Tree was visible between the larches.

Fran and woef took Obsidian’s life and I did not see him die.

In the fresh spring grass with Lucy, I fed and petted her.

The community that I grew up inside held few secrets. Everybody knew each other’s business. The occasional passage of an ambulance would be a source for intimate concern. An elderly man, drunk in the street, was to be buoyed up on all four corners by women of differing ages, and every one of them would know his name – in all probability his middle name as well – not to mention the address to which they needed to return him.

The ‘local’ was an archetype that to me offered excellent blueprint for the ‘societal’ which must, I thought, be its logical progression. Technology had upscaled what local meant. Brought up with a deep-seated loathing of the nationalistic, which has never left me – an inescapable understanding that it is defined in antagonism of the other – it was perfectly natural for me to place my belief in international law.

Capitalism has no answer to the tragedy of the commons, but international law does. Colonialism cannot be redeemed by virtue signalling, but international law can redress the pillage. Without a bill of human rights and an international court, what remedy was there for nationally sanctioned crimes? I had never had reason to question the concept of global governance.

Here, in the vegetable garden, I water parsnips and spend my days mulling over the things that the world has shown me since 2020.

Today’s ambulance goes past at 9.06 am.

Recondite is one of the most beautiful words I know. My daughter gave it to me. “Hidden from view,” she read to me aloud one day. “Concealed, profound.”

I love words more than I am able to tell you through the use of them.

Perhaps to try would be unnecessary because you feel that love yourself. After all, they are really only living symbols – existing inside each of us, unboundaried and companionate – waiting for the cultivation language can bestow.

Outside, the Darlings are Happy in a Nice Place now, and the Baby Darlings equally so in their Nice House. The occasions are numerous when I sit down to write and am prevented.

Overleaping, squiggling under, crushing fence lines and breaking tethers, the Darlings aim to be Naughty as if in intentional protest.

I put them back. I reconstruct the walls. I lock. I barricade.

“Happy,” I once again apprise them.

At the laptop, straying into Twitter, my own emotions are snagged and tightened. Identity politics and international economics abound. The words are loaded:

#New World Order. #TERF. #CulturalMarxism. #FarRight

What’s in a name though, really?

Is it enough to separate us?

Bill Gates, I read, is a Marxist now.

I have had cause to think anew about the economic and governance structures that underpin my world as the last two months have elapsed. Its 75th anniversary drawing closer, I’ve had reason to think about Britain’s welfare program in general, but in particular the history of the NHS.

We discovered the lump in the back of my daughter’s mouth on the 10th of May. She told me her throat felt cold. Opening her jaw wide to show me, the obstruction inside was immediately visible, blocking her windpipe fully from her uvula to one arched pink wall; closing up fifty percent of her airway.

She wasn’t ill – nor did she become so. For a week, I high dosed her with vitamin C and the words on my mind were strep throat, but as the days went by, no sickness came – and the lump did not go down. Eventually other words began to come to me.

She started to choke on it when she lay down. A crying jag – which, as she’s ten years old, she cannot avoid sometimes – transformed itself into a choking fit that would not end. We took a trip to A&E. The doctor saw us at midday and we were immediately referred, the ENT specialist saw us by 8pm, the consultancy for the operation was set in motion by the end of a single day and, though no one had used the word tumour, by that time I understood.

Had she lost weight? Was she experiencing fatigue? I looked it up: asymmetric asymptomatic tonsil swelling. Ear Nose and Throat specialists are trained to treat any presentation that matches such a description as cancer. I’ve witnessed throat cancer before. It was three months between diagnosis and death. Malignant or benign, she was sometimes struggling to breathe around the lump or safely swallow. For two weeks, without mentioning to her any possibility that might make her afraid, I lived with her fear instead. I swallowed it for her. I managed to hold it down.

She started saying that she couldn’t taste anything. The roof of her mouth had lost sensation. With no letter in the post, no registration yet with Gwent outpatients department, I paid £150 to book a separate consultant’s appointment. Clearly this was the way through the maze of contact numbers written in capital letters across my A4 page.

I packed us a picnic and an overnight bag and drove us to Cardiff. In the waiting room, she counted animals on the map on the wall; first blue ones, then green ones, carnivores, then omnivores. I watched the consultant’s door close and open.

It was a beige door with the name of the specialist neatly displayed and behind it was the room in which I would hear whether or not my daughter could be taken from me.

The layers of the world peeled away and there, underneath the actions of my moving body and the things that had to be done throughout the day, was this reality. There wasn’t anything else above the raw surface of existing.

Aneurin Bevan – the great Welsh orator, social reformer, father of the NHS – lost his own father to pneumoconiosis; coal miner’s lung. He began his firsthand experience in the coal mines of Tredegar at thirteen. “My heart is full bitterness,” he would say later, “for when I see the well-nourished bodies of the wealthy, I also see the ill and haggard faces of my own people.”

The NHS was modelled on the Tredegar Medical Aid Society. I learned this for the first time just last week. In constant physical danger, abused by industrialists, desperate for work in the communities that had formed around the mines and devoid of rights and benefits, Tredegar working men clubbed together. They gave tuppence each week from their wages towards their own tiny healthcare system. Even a hospital stay in London would be covered for them if they had such need.

This was the model with which Bevan grew up.

He gave only one speech to the Fabian Society that birthed the political party he’d joined in order to kick his way into government. Its subject was democratic values. In it, he urged Labour’s ‘gradualist’ mentors to secure the financial means necessary to ensure our young democracy was able to continue bringing about fairness.

During the speech, he had been, he said, “careful all the time to express myself with sufficient ambiguity where the ice looked very thin.” For more and more of the world’s goods to reach the individual in some other way than by the haggling of the market, constituted, he said, progress towards a civilised standard.

We visited Tredegar House, my daughter and I – “the grandest and most exuberant country house in Monmouthshire” –spending the extra hours before her diagnosis, which I’d ensured we’d have in case of traffic problems. In the sunshine, we wandered the National Trust-owned grounds, saw the ornate and intricate construction of the mansion’s brickwork, sat on the grass and swung together on the playground swings.

Its many windows were blue with another day of sunshine. It was still owned by the Barons Tredegar the year that Bevan gave that Fabian speech; its graceful days of sunlight still gated from the miners’ adjacent world.

I can’t find corroboration in my research – perhaps you know – but I’ve been told that Bevan wished to nationalise the pharmaceutical industry too.

Today’s ambulance goes past at 12.26pm.

Our operation is in the wings now, we are told. I have navigated the triumvirate of British healthcare; public, private, group. The lump in my daughter’s throat is not a cancer.

The consultant was careful and thorough and kind to us both, but particularly me, I think. My little girl was telling him all about the animals.

A prolapsed tonsil, he said. He would take them both out and, he assured us, lying in a silver dish, they’d be absolutely equal in size – it was just that one was sitting inside her mouth now. We are working hard to prevent any crying jags and we are waiting as patiently as we can. The NHS paediatric list is the most urgent list there is.

He told us he’d put money on the diagnosis.

This morning I shell peas for my daughter’s lunchbox. Rotund – grown to fill all space they have been offered by the world – I try not to pierce their surfaces as I uncase them.

Over the many days as we waited for the appointment – which were planting days, seventy cabbages and fifty parsnips – I placed one hand in front of the other and I thought about what it meant to live. What it meant to live in fear and maybe beyond it. I planted the food to eat, which would allow me live, in order to plant the food to go on living. And acutely like this, I felt the existence of our world.

There is a conception of the universe, which is held by occultists and physicists alike, that visible matter constitutes no more than the alignment of a spectrum which is in fact magnitudes greater - but to which we are insensate.

Like words, what we touch and hold and interact with are but living symbols upon the depths we cannot cultivate inside the world.

Fran and I keep antibiotics in our medical boxes. My box, upstairs in my bedroom, is three foot deep and four feet long. It contains everything, from six months’ supply of L Ascorbic Acid and N Acetyl Cysteine to trauma dressings to a moon cup purchased in expectation of my daughter’s eventual puberty. In 2021, it was suggested in parliament by the presiding Health Secretary that those who refused the coronavirus vaccinations should not only be shut out of day to day life, but also the NHS.

The society that I had known had parted from me without resistance. I stood outside arts venues and gazed at the posters that advertised performances accessible only with a government code. I listened to fellow artists tell me that they had acquiesced to the injections because they just wanted it all to end. I watched my closest friends place gingham cotton across their faces and nod at a distance of six foot from me. And I nurtured the garden that I might need so that I could feed myself and my child.

You cannot maintain a healthy democracy supinely, Bevan said.

The NHS Trusts wrote letters addressed to children as young as six years old, the Telegraph later reported, urging them to take the mRNA injections, the trial results of which Pfizer was attempting to bury for a 75th anniversary too.

Just previously, the Trusts had applied Do Not Resuscitate Orders on a blanket basis to PCR positive inpatients too weak or elderly to know what was happening to them, then in many cases set “end of life care” in motion.

Protect your grandparents, children were told.

Fran and I approached a neighbour who worked as a paramedic in 2021 with an idea identical to that of the Tredegar Medical Aid Society – despite the fact that neither of us had heard of it back then. Not tuppence per week each, we thought, at the beginning of the 21st Century, but maybe twenty pounds.

What has become of that local seed, I wonder as I tend our garden.

Surely this is not its harvest.

Now that the former head of the Bank of England has become the steward of our global biosphere, it should be clear to all that we are reaching the apex of international government. But as our own small lives are overwhelmed by crises and costs – or dazzled by the whirling words and GIFs and memes of “social” media – it can be difficult to interpret what this governance actually means.

Luckily the United Nations has produced a handy chart, navigable to all of us.

Diverse and inclusive – rainbow beacons of a species-wide goodwill – here’s a set of goals the human populace can take as read without reading.

What’s in a name?

Impact economy? Stakeholder Capitalism? Global Public Private Partnership?

I find it impossible to picture Bevan existing in the 21st century. As if the raw silk of his words could not be uttered, or heard, in a world so riven by algorithmic winds.

The restructuring of our language – our means to commune – is demolishing our capacity for both community and meaning. And in the midst of our confusion, the greatest ransacking perpetrated in our history is starting to take place.

Each of the UN’s colourful logos is backed by a team as adept in their field as Mark Carney is in meteorology, and each one has a remit and a marketing budget that’s just as broad.

As we “abolish poverty” with the institution of conditional currencies, controlling the behaviour of the poor and betting on them in impact markets, as we financialise nature in order to ensure “life under water” and “life on land,” or create “sustainable communities” through constructing checkpoints and unrolling surveillance grids, it would be natural for us to ask how the institution of a program so profound, so all encompassing, came to be with such ease and precision.

The New World Order unfurls with the perfection of genetically engineered seed.

‘Mumma’ was my daughter’s first word, as with most children, meaning both myself and the milk I could provide. She extended her voice towards me in the same way she learnt to extend her hands.

Next there was ‘Ni!’ – an expression of negation.

At the cooker on my hip – twelve months old and moving past breast and formula – she waved at the white surface warming in the pan and perfectly sounded two syllables: “Ready.”

As it does in every one of us, the seed of her language uncurled.

The Occult – which itself of course means ‘knowledge of the hidden’ – holds that a word contains the essence of the thing it names. The vibration made by its pronunciation is its link the between the etheric and material worlds.

One can only wonder at the views of C21st occultists on the deliberate dissolution of meaning.

Plato, the philosopher king so admired by occultists – or theosophists as they prefer to identify when in consultative status with the UN – designed a utopia predicated on absolute governmental control. In The Republic, his state of perfection was to be achieved across a multifarious population through the limiting, not only of choice, but of the conceptual language necessary to it. No future soldier was to be confused with the wrong type of music, no fable or legend accessible to a child unsupervised by the state. Most of the stories in use at that point, he decided, would have to be abandoned.

“If there were a more exact science of government, and more certainty of men following its precepts, there would be much to be said for Plato’s system,” Bertrand Russel would write some five hundred years afterwards – during one of the gaps in his social calendar between Fabian Society meetings and the CND.

Rhabdomancy, impecunious and rille are words which, somewhat surprisingly, Microsoft Word has sanctioned as being part of the conceptual framework of the English speaking world.

Ok, not rille. I lied about that one. But I didn’t want to take it out.

Rhabdomancy is the practice of dousing using a divining rod.

Impecunious is a word that I have sorely needed for many years – and which I suspect others in my state are also lacking.

Rille is a furrowed valley carved upon the moon.

These three words were also gifted to me by my daughter. We have a rule: she is allowed to swear – using the crudest, most offensive four-letters she can find if she wishes – but afterwards she must use a Nuttall’s Dictionary to present us with a word that we have never used before.

Swearing is powerful. It takes people aback – particularly from the mouth of a ten year old. But it’s nothing in comparison to pronouncing rhabdomancy in the right place.

Language is power, my daughter now also says.

I right click on rille. I add it to the Microsoft dictionary. I feed the beast that so far still sits tame. My world is not only richer for these three words, it is in clearer focus. The evolution of ours species – written in uncountable novel comprehensions – reaches out to touch our universe on every side.

And the Microsoft dictionary? The AI powered Bing?

We touch our universe because we find it beautiful. The beauty of our experience – as powerful a force as Dawkins’ supposed selfish gene – chases not self-replication, but reception. Communion, not conquest. It looks for oneness with our world.

Our farmers have been busy for many decades now. Amidst their unsustainable system, which has already despoiled our world with their greed, the “collectivist” solutions now being sold to us with fun and brightly coloured monograms are the antitheses of the socialism for which Aneurin Bevan warred.

The UN’s birthday party messaging is simple for a reason. It wraps the totalitarianism that has been inherent in the UN’s agenda from the outset in a packaging uncomplicated enough for even “mental defectives” to receive.

Hampered by the reputational damage done to eugenics by the Nazi party, Julian Huxley had to spend a lot of time attempting to solve the problem of such defectives remaining in the gene pool when he wrote UNESCO’s founding document. Luckily, Aldous’ brother was a dedicated man.

Assuring the United Nations’ new Education, Science and Culture team, his zeal for his work was too great for me to paraphrase:

“The dead weight of genetic stupidity, physical weakness, mental instability, and disease-proneness, which already exist in the human species, will prove too great a burden for real progress to be achieved. Thus even though it is quite true that any radical eugenic policy will be for many years politically and psychologically impossible, it will be important for Unesco to see that the eugenic problem is examined with the greatest care, and that the public mind is informed of the issues at stake so that much that now is unthinkable may at least become thinkable.”

And just in case you’re in any doubt as to the veracity of my citation, here’s the link again. Page 21.

Fran lives on the rural A road that takes residents from our sparse county to the closest hospital, over the border in Hereford. She tells me there are as many passing ambulances that flash in silence now as there are ones from which a siren wails.

My daughter’s healthcare care record is a small red vinyl book with neat ticks and dates beside each immunisation. She leafed through it with fascination as we sat waiting outside the Spire Healthcare Group’s headquarters. The sun was shining, as it had been without impediment throughout the day. In fifteen minutes, we were due to finally meet with the consultant, but in the meantime she sat cross-legged on the lawn, reading me questions from the red book’s pages – which I’d answered once already, a long time before this.

“Are you feeling well yourself?” she said.

And I smiled – successfully, I thought.

“Are you happy that your child is growing normally?”

I watched her move the hair from her face so she could see the page more clearly. “Yes,” I told her.

“Does your child understand when you talk to him or her?”

“You seem to get most of the things I try to communicate to you,” I said.

In the sunshine, she laughed briefly.

“Do you have any worries about the way your child talks?” she read.

In every seed, there is an unknowable core of life – that animates its growth as it looks for air and water. The value of a living being is in its expression of this spark, not its service to the whole. Humans, as much if not more than any other creature on our planet, express a symphony of unique connections to the fabric of our universe. And the value of this multiplicity is something of which our farmers are aware.

I garden species. I have sown my own seed potatoes for the first time this year. I pluck from the flock those of violent temper or those who stray. I am concerned in the course of my work with the limits to growth. It is better, I know, to keep fewer animals with better care.

As Sustainable Development Goal number three – Good health and Well-being – increasingly forces ‘debt restructuring mechanisms’ onto low and middle income countries, pressuring them to accept the blanket use of ‘medical counter measures’ like vaccines, fattening the balance sheets of pharma giants and allowing their investment ‘partners’ to hoover up assets in the case of defaults, we ought not to hope that, here in the Global North, their motives are less obscene.

Across the flowering web of the WHO’s ‘stakeholders’, the collation of our global healthcare records – a far cry now from my daughter’s floppy-leaved red book – will embody an entity of global governance that it’s not in the least surprising to see the UN’s favourite ‘consultative’ occultists cheer-lead in:

“Ageless Wisdom perspectives look to the evolution of humanity in terms of the growth of a wise, inclusive, and intelligent consciousness actively working to organize human affairs,” the theosophists mingling at UN conferences inform us.

Health data, like all ‘impact’ data – educational, work-based, welfare driven, or gathered from the biometric signatures of our children’s first spoken words – will be combined into an overarching ‘consciousness.’ The selfish ledger, Google calls it.

An inanimate, aggregate, blockchained mind.

We all want to be part of a society – and in that find meaning. Over and over, I meet people who succumbed to social pressure in 2021. “People told me to protect my mum.” “I did it because I felt like I had to.” A woman in a local shop with untreatable sores all over her body now. A girl who works at the doctor’s and whispers in case she’s overheard.

But this is our society. It does not belong to the engineers who aim to shape it in accordance with their philosophic or profiteering goals. It is not the externalisation of their hierarchy.

It grows from communality and neighbourly love, from independence and compassion. It is the natural flower of our local seed.

It’s the time of year now in the garden when the voles attack from underneath the ground and the blackbirds land to steal what fruit there is above it – and my mother and I try not to sit with heads in hands. A gash under Thorne’s udder – cut on some poor timber, four times used and still stuck with nails – leaves her two boys tethered and milkless and shouting. Their bells ring loudly and, in the scraps of silence left behind, I weed the dry, cracked ground and quietly consider the two words, ‘free.’

Those who know, and care, have recently told me to write on other subjects. To cut the politics. But I am writing in the hope you’ll hear. I want to reclaim the society that was taken away from us in 2020 and consolidate it for our children. I want us to define the meaning of community.

Driving home from dropping my daughter at the school gates this morning, as I turned onto our lane, a family of young ducks obscured the path ahead of me. They looked, I thought as I drew to a stop, like the Indian Runner I once lost. Very close to the threat of the main road, I wondered momentarily how I might herd them up and take them home to somehow protect them.

And then I watched them fly.

Endangered briefly as they made their way out onto the deserted tarmac, they took off one by one. And I thought of my muscovys – not enclosed by any fences, their wings never having been clipped – awaiting the feed that I would give them that night as they sat in groups around my lawn, without the thought-form necessary to outline the concept of freedom.

June has come and gone now. The hawthorn has slowly blushed and lost her bridalwear. I’m looking at the last of the summer and haymaking soon.

I send you love. I hope you have good people around you. For all our ups and downs together, I am treasuring mine.

I know what it’s like without them; to feel or fear their loss. I will never forget that late afternoon with my daughter, the sun lowering behind Tredegar House two miles away from us, where we sat on the grass, waiting patiently for her diagnosis amidst the many daisies, each of their faces turned expectantly towards the sun.

Images by Francesca Swift and woef .

With special thanks to Alison Mcdowell.

Yes! Thank you, for your commitment to writing some political truths that are uncomfortable, maybe dangerous, and integrating this writing in to your very real life, and for acknowledging Alison McDowell whose work is so challenging but important. And I don't want you to apologise for not writing more, because your real life is so grounded and can only benefit us more when you do get fingertips to keyboard. Love to you and yours from this separation, through this connection of heart and mind. Your writing nourishes me, and stretches my heart, and eases my soul.

Beautiful. Has enriched my day, thank you 🌹