Hello!

Welcome to Walking With Goats, an understandably irregular column covering all the things you would expect from the title:

- Guerrilla Grazing (and stories thereof)

- Epistemology (from the point of view of someone who finds knowing things difficult)

- Politics surrounding the issues of enclosure (based on very little historical accuracy – see Epistemology)

- Reminiscences of a hippy, smallholding childhood

- Dispatches from the frontline of a violent and inevitable war between rewilding and self-sufficiency

- Pictures of goats

- Prompts to read my serious fiction

- Suggestions for donations to feed costs

Other things you may come across (some I hope with the swift poignancy of a forgotten photograph, some perhaps like last week’s banana in your child’s school bag):

- Ruminations on the 21st Century state

- Negative efficacy preservation recipes

- Poetic language that tries to express my incredible good fortune at spending every day in an (albeit often muddy) paradise

- Pictures thereof

- The grief of Cassandra over advancing global agendas (Natural Asset Corporations, the blind sacrifice of rights and solidarity in search of an elusive feeling of safety, saying bye bye to our children as they run giggling after Mark Zuckerberg’s shit avatar, the smiling mask of carbon neutrality over a rural landgrab by the world’s biggest monsters)

- Orthomolecular medicine

Or maybe just goats.

I will ensure that I follow up any of the items on this list, if they occur, with more pictures of goats, stories about goats and genuine insight into the habits and attitudes of goats. Although to be honest, walking with goats has a lot to say about all of these subjects.

There was a question that managed to percolate through the exhaustion-numbed swamp of my mind after two years of attempted self -sufficiency:

If land use was agrarian, would we have no intellectuals, or seven billion of them?

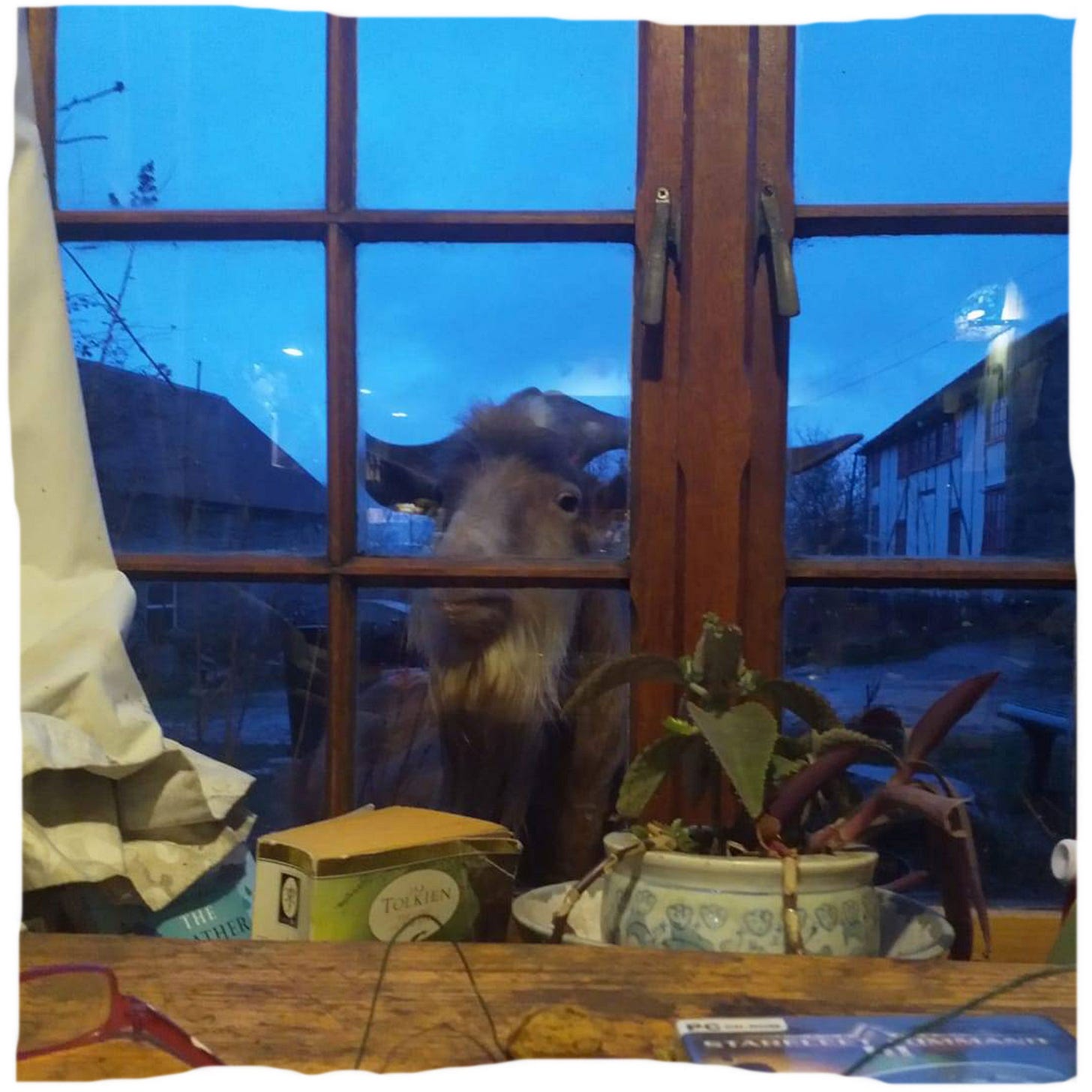

Before we get into it, here’s a picture of a goat:

Great.

Now let me tell you about a thing I actually said to my daughter once:

“As privileged Westerners, some of the most important choices we can make are the things we buy.”

This is the kind of paltry dust of existence that characterises spiritual famine. This is chaff scattered over Netflix’s dark barn floor.

Some of the most important choices to whom?

We form in constellations, shaped by family, by culture and geography, era, class, fitting our ‘self’ across the space around us over the course of a lifetime. We scribe it in equations of epigenetics or sing it in folk melody, colour it with in-jokes and, these days, paper its unsound inches with selfies, status updates, emojis, avatars that not long from now will twin us, in as much as we are able to be known.

We are our place in the ecosystem. I think at the time I meant ‘important’ in terms of the effects our consumer choices had on the world. We vote with our money. The billionaire class is totally elected. But even in this direction, the import’s a wan gesture towards relational meaning. Unless you’re Elon Musk, your individual boycotting or buying effects the whole only as much as it sits within a common voice.

And in the other direction?

“Some of the most important choices we can make are the things we buy.”

Imagine if this was the talismanic jewel of wisdom my daughter selected to carry forwards with her into adulthood. Fully grown and making her own way in life, strategically orchestrating change within her society and coming to know the still waters of her own self through a nightly selection of plant based burgers.

Let’s take a minute to look at a goat.

Sanguine aren’t they.

(No goats were injured in the making of this blog.)

When a supposedly thinking human articulates a life-gift like this to their only child, it’s safe to say there’s value missing. The third condition of mass formation has been met. This isn’t meaning-making.

So now we could talk about a potato, or we could talk about hay, or maybe spices. There have been several times in my life that meaning has welled forth from prosaic things, broken them open to disclose a profound or visceral beauty. A rack of spices – cumin and cardamom – abandoned inside a derelict building where I once went to live, that conjured tones of foreign seas and souks to me that no jar on a supermarket shelf had ever been imbued with. They were so precious, there in the dust over the electric oven. Or maybe the potato, which any gardener knows is treasure unearthed, joy coming up into the light for the first time. Or hay, a field of which I turned and gathered by hand last year. Self-sufficiency as meaning-making. Maybe I want to be valuable. Maybe I thought that if I saw the value in what I consumed, mapped between them I would have value too.

The hay meadow is just over an acre in size – one of eight acres that according to the Land Registry belong to us – replete with yellow rattle and red clover and many species of meadow grass. Unreally vast in front of a pitchfork, freshly cut. Small in terms of the productive capacity necessary to sustain a year-long supply of meat and dairy for my immediate family though. Perhaps one third of the total hay needed for the flock to the survive the winter. Raising your eyes to the boundary, such a slice of land can suck your limbs of life and still not produce enough to sustain you.

My mother – who dedicated her life to rewilding long before the term was commonplace – might tell me that the reason such an equation seems insoluble is because it’s asking the wrong question. Unfortunately she’d probably tell me this over a plate of imported lentils, so I wouldn’t listen to her. In some ways, this is the tale of a mother and a daughter at odds with one another.

In the midst of uncountable green and gold plaits of cut grass, I did find meaning. I suppose a kind of God. One of hope and grace and fear, the acceptance of helplessness. It took nine days in the hottest sun of the year. This was the end of July. Small balers are rare now and the contractors that service most farms with large balers don’t wait for the dropping seed that constitutes the real wealth of this acre. The only way to gain the hay while sustaining the meadow was to take it myself.

It's not a rectangle but a kind of crescent against our woodland and house, this space that’s both too much and not enough. The God presiding over such a map of enclosure is one of implacable – if beautiful – judgement; perhaps the only kind possible to incarnate with pastoral faith.

This is the God who will answer if the question shaping your existence isn’t only how can I take all this? but how can I take more?

It is not the God of guerrilla grazing.

Bertrand Russell had this to say about the relationship between epistemology and guerrilla grazing:

…Religious truths which can be proved can also be known by faith. The proofs are difficult, and can only be known by the learned; but faith is necessary to the ignorant, to the young, and to those who, from practical preoccupations, have not the leisure to learn philosophy. For them, revelation suffices.

Obviously he didn’t understand at that point that he was touching on the subject of grazing. I was clear though, when I did find time to go over The History of Western Philosophy, that he was talking about me.

I am not an intellectual. I am not one of the learned, no matter how much time I dedicate to trying to learn things. My mind is a ferment not a computer. Life gets input, nameless ruminations occur – a coagulating string soup without concept badges – and sometimes fiction comes out, and sometimes people want to read it.

I’m also not a person of faith. I did feel though, in the midst of all that green and gold, the sensation of revelation. In fact through the entire shit storm that has constituted my journey towards feeding myself, revelations have come. Many terrible. The wealth of thought and feeling and understanding gifted by the God of such lives is not penny-counted by the semantics of the ontological argument. It is the God of feast or famine.

Obviously I didn’t have much time to write down what I had to say to Him then. Thought is profit and the only reason I’ve ever had a few is that someone else was doing the labouring for my food.

This is the long-supressed relationship between epistemology and guerrilla grazing.

If I’d been able to put the pitchfork down and cogitate a little both on my “practical preoccupations” and any profit thereof, I might have asked the Heavens and Whomsoever Was Available At The Time whether it might have been better to just walk out the gate.

If thought is profit, is intellectualism profiteering?

I’d ask Bertrand Russell – or as I like to call him, 3rd Earl Russell – but I don’t have his direct line.

Let’s spend some time with a goat.

This is Thorne.

Thorne is our flock’s queen goat. Goats are matriarchal and Thorne is an archetypal queen, stoic and unassailably certain of herself. When she bleats, it is always the same bleat – three descending notes – of deigning to assent.

If Thorne wanted to talk to God, she wouldn’t need a mediator.

It’s a commonly held misconception that foraging societies raised their standards of living by turning into farmers, and more on this festering pile of assumptions later (probably along with what it did to our sex lives). In fact, modern Europeans still haven’t regained the 5’9” frames enjoyed by their pre-agricultural forebears. Farming must have had some seriously successful PR to handle that damage control.

Outside our fences, the world’s a big place. We conceive of the commons as an unhindered plain or an ocean panorama – and did you know that everyone in it could fit in their own bungalow in Texas? That’s not the kind of suburb I’d want to live in, but it helps to illustrate the sheer scale of the place. And beyond the great, the small: there are interstices of abundance. There are wellsprings of life, of compost, of death and rebirth, of health and wellbeing in every hedgerow.

I think I’m arriving, on an appropriately meandering timetable, at the voluminous bramble of enquiry I’ll probably nibble my way around for some time. If land-is-food-is-time-is-thought then there ought to be such opportunity for rumination now. Between the well-lit aisles of milk extracted from herds fed by grand machine, we ought surely to be better able to talk to God. Or Bertrand Russell.

I’d better run. For me, there are goats who do not want to be enclosed and have a bone to pick with those who put up fences. So I will leave you with this sacrament from those who now geofence our knowledge, and I will go off to guerrilla graze and stir my idea soup.

You've sold me on the goats. I'm going to look into getting a couple. I expect homemade goat's cheese would be fabulous.

That's really kind Christina - thank you. I hope you enjoy the others. Sharing the experiences makes them worthwhile.